“I have used similitudes.” – Hosea 12:10

Reading but the first few sentences of The Great Divorce, I remarked aloud, “Oh, here we go,” for I knew that I was now launching into one of Lewis’ most controversial books, the one about Hell. I had never read it previously, but was familiar with its speculations largely by way of the many remonstrances I’ve received when mentioning Lewis name among the orthodox.

“You do know that Lewis was wrong about Hell?” This always seems to me a rhetorical question of the order of “Am I my brother’s keeper?”, with the interrogator never really meaning to ask, only to inform. I have heard it asked and answered enough over thirty years in the faith that I came to this book tangentially aware that Lewis at some point opined that the damned in Hell might not be permanently sentenced there, and that souls might yet have an eternal series of chances to true up and get to Heaven. I had heard often of Lewis’ “bus” that regularly passes by the transit stops of Sheol offering passages to Paradise. Lewis, it was said, thought of the damned as simply being yet too self-absorbed to desire Heaven. They will continue to live willfully in a lackluster, run down, grey, uninteresting place, forever, by choice.

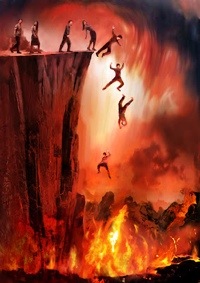

Such a suggestion of course flies violently in the face of Christian orthodoxy and sound biblical doctrine. Jesus had more to say about Hell than anyone else in The Bible. Without turning this post into a sermon on the same, suffice it to say that scripture clearly establishes that Hell is a place of eternal fire, pain, torment and tears, and not just some distressed afterworld rust belt community. Further, it is a lock-up after life. The Bible is clear that we get only one chance, in this earthly life, to acknowledge God’s sovereignty over our lives. There are no open tickets at the help desk of Heaven.

“And just as it is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment” Hebrews 9:27

So, what are we now to do with Lewis? Having actually read the book about which some of his harshest criticism has arisen, I’m inclined in charity to cut him a measure of slack. The testimony of Lewis scholars better steeped in the entire corpus of his letters might be able to prove me quickly wrong on this point, but my own sense in reading The Great Divorce is that Lewis didn’t necessarily intend this book to be a doctrinal treatise. He was emphatic on this point in the Preface:

“I beg readers to remember that this is a fantasy. It has of course — or I intended it to have — a moral. But the trans-mortal conditions are solely an imaginative supposal: they are not even a guess or a speculation at what may actually await us. The last thing I wish is to arouse factual curiosity about the details of the after-world.”

In representing an exchange between an heavenly being and an “Episcopal Ghost” visiting from Hades, Lewis writes:

“‘Well, this is extremely interesting,’ said the Episcopal Ghost, ‘It’s a point of view. Certainly it’s a point of view. In the meantime…’

‘There is no meantime,’ replied the other. ‘All that is over.’

And on Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he observes:

“The attempt is based on the belief that reality never presents us with an absolutely unavoidable ‘either-or’; that, granted skill and patience and (above all) time enough, some way of embracing both alternatives can always be found; that mere development or adjustment or refinement will somehow turn evil into good without our being called on for a final and total rejection of anything we should like to retain. This belief I take to be a dangerous error.”

All this seems reasonably orthodox to me.

Lewis was possessed of an extraordinary imagination. In The Great Divorce he employs that imagination to create another of his marvelous illustrations to help us better understand why a loving God would permit anyone to spend eternity apart from Him, much less in torment. His conclusion: for most of them, by reason of their own preference. To illustrate this point, Lewis imagines that Hell’s residents are afforded “excursions” to Heaven to check it out, as if they were responding to a three-night stay at a timeshare community to hear the sales pitch, again. By following the “tourists” interaction with Heaven’s constituents we come to see that Lewis isn’t, I think, so much suggesting that the damned actually do get a second chance, only that if they were shown such a reprieve they wouldn’t take it anyway. He offers a line I believe I already encountered in one of the earlier books, but it is fittingly recalled here:

“There are only two kinds of people in the end: those who say to God, ‘Thy will be done,’ and those who to whom God says, in the end, ‘Thy will be done.'”.

One suspects the unorthodox, some say heretical, ideas of George McDonald influenced Lewis significantly in the writing of The Great Divorce. The traveler narrator happens mid-way through the story upon the old Scotsman as one of the heavenly residents, and McDonald commands a substantial part of the dialogue thereafter. It is McDonald who tells the traveler narrator of the “holidays of the damned,” the “excursions” they get to take back to Earth and to Heaven. Just as you are ready to castigate McDonald for filling Lewis’ and through him our own minds with such heresy, McDonald offers the traveler a line of thinking worthy of ponder.

“…both good and evil, when they are full grown become retrospective. Not only this valley but all this earthly past will have been Heaven to those who are saved. Not only the twilight in that town, but all their life on earth too, will then be seen by the damned to have been in Hell…both processes begin before death.”

In essence, from the vantage points of Heaven and Hell the retrospective views will cause all of life, temporal and eternal, to appear as either heavenly or hellish, all along. This does makes one stop and think, which of course was Lewis’ aim in authorship. I myself, at first blush, can’t dismiss this particular speculation as unbiblical.

The Puritans warned of the use the imagination, equating it with idolatry and the graven image-making prohibited in the Second Commandment. Yet, while John Bunyan sent The Pilgrim’s Progress to publication with a prefatory apology for the expression of his imagination, he noted that even God communicates in “similitudes”

Herein lies the rub about Lewis and The Great Divorce. In permitting his imagination to explore an alternative reality to Hell, he played with fire of an eternal intensity. In an exchange one of his hellion remarks:

“They lead you to expect red fire and devils and all sorts of interesting people sizzling on grids —Henry VIII and all that — but when you get there it’s just like any other town.”

Hell, however, is not like any other town. There is fire and there are devils. For Lewis, who had already by now established himself as an apologist for the Christian faith, to steer seekers away from Hell’s harsh realities, even in a flight of literary fancy, is tantamount to using his imagination to cause children to consider alternative ways of playing in the traffic or the rest of us to believe that handling nitroglycerin might not require as much dexterity as we were previously lead to believe.

While, again, I am not yet convinced that this is what Lewis actually believed of Heaven and Hell, I have encountered enough Lewis devotees who will say, “Well, you know Lewis believed that those in Hell, &c., &c., &c.” The Great Divorce does a marvelous job of causing us to consider just how powerful are the sins of Pride, Vanity, Unforgiveness, Idolatry, and others — so powerful that Lewis’ imaginary damned in Hell won’t even trade them for sublime joy — so powerful that many will remain in their sin even when the Son of God returns and reveals himself in glory at Earth’s last days. We can certainly credit C. S. Lewis with causing us to appreciate sin’s horrible grip. He just didn’t need to minimize the horror of Hell itself to do so.

Pater Familias

S.D.G.